The Evolution of ADHD Diagnosis

The Why

Welcome to "The Things We Didn't Get To," where we dive into the topics that might not be fully explored during a typical appointment time. Today, we're exploring the evolution of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) diagnosis. Understanding the history and changes in ADHD diagnosis is crucial as it has greatly shaped who and how we diagnose people. Notably, females at birth (AFAB) were often missed in the creation of the criteria, diagnosis, and treatment.

The Info

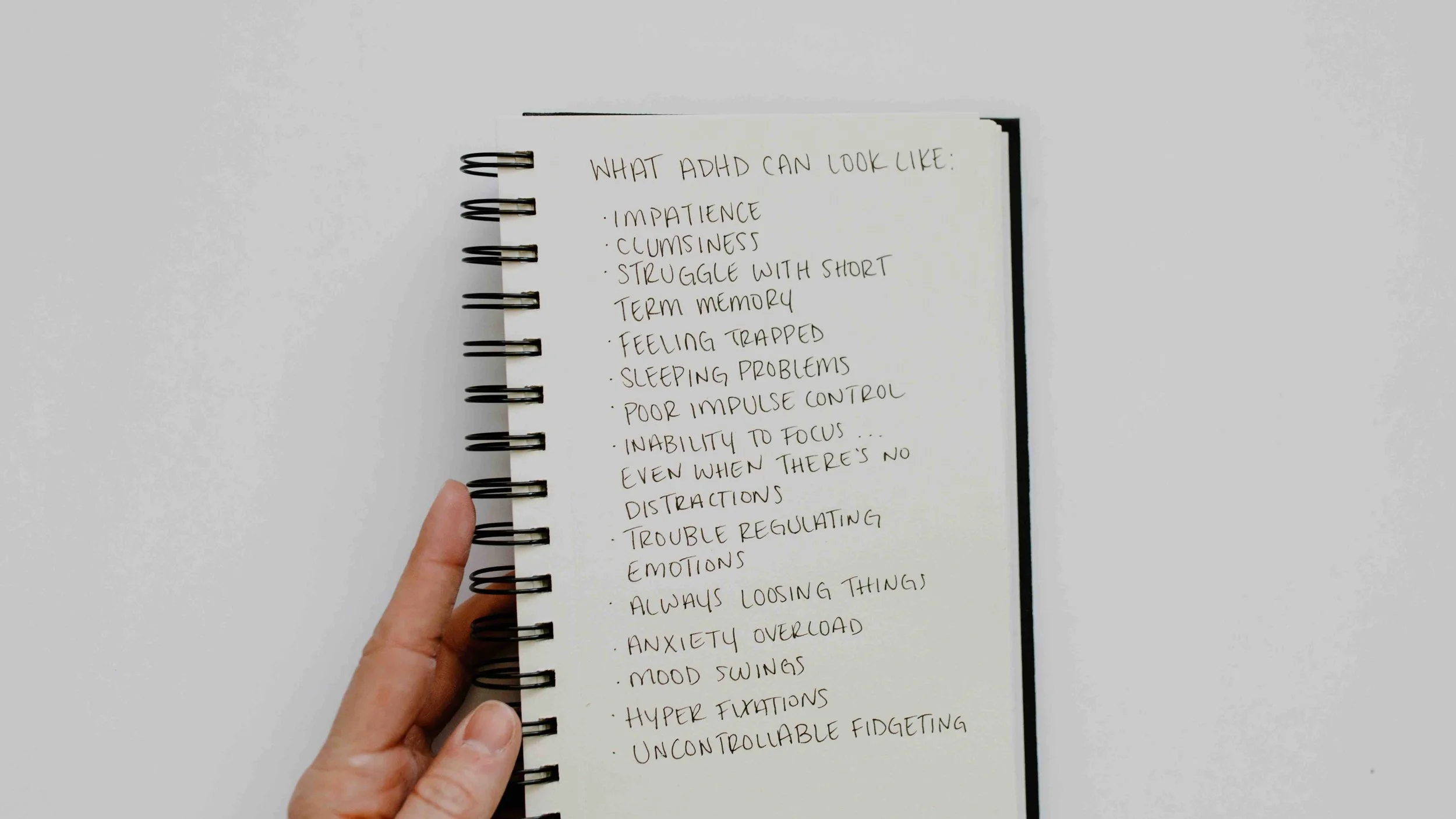

ADHD was initially identified in the 1950s as "Hyperkinetic Impulse Disorder" in the DSM-II, emphasizing hyperactivity and movement as the defining criteria at that time. It was later changed to "ADD" in 1980 with the new concept that hyperactivity may or may not be present, and inattention was recognized as the main presenting pathology. We still often hear it called "ADD" by clinicians and patients alike because "I don’t have the hyperactivity." In DSM-III-R, published in 1987, the diagnosis was changed to "Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder" or ADHD, further acknowledging the role of hyperactivity and now including impulsivity. It was largely thought to be a childhood diagnosis that would "resolve" during adulthood, often cutting off treatment at 18 years of age. Fast forward to the DSM-5, ADHD was changed to include three presentations to be more inclusive of the ways ADHD may present differently. The three presentations included inattentive type, combined type, and hyperactive type.

Despite the advances over roughly 50 years, the DSM-5 still largely characterized the diagnosis as a childhood diagnosis and did not address the significant differences between AFAB and males at birth (AMAB). The DSM-5-TR released in 2022 moved to better characterize ADHD as a lifespan diagnosis and helped to capture later onset (less externalized) symptoms that are actually common in the AFAB presentation. It changed the "presentations" to "subtypes," recognizing that ADHD could be diagnosed as co-occurring with Autism.

Discussion

The history of the diagnosis of ADHD is complex and highlights many larger, problematic themes in the field of medicine and psychiatry. One important theme to identify is the initial diagnosis in the 1950s only captured what could be seen, which speaks to the ongoing struggles of invisible disability. It also highlights that psychiatry often only pathologizes presentations that are problematic for society instead of what is problematic for the client. For example, the kid who is disruptive may access care quicker because it poses an externalized problem for the teacher and peers. In comparison, the kid who is daydreaming and can’t track a lesson for longer than five minutes will not be diagnosed until adulthood, enduring a childhood of being identified as "lazy." Later diagnosis is strongly associated with worse outcomes. It is important to shift assessment and criteria to capture the internalized experience of the client while not entirely discounting externalized behavior.

Another key takeaway from the evolving criteria of ADHD and what remains problematic is that the current criteria still heavily emphasizes the original AMAB characterization of the diagnosis. A study that came out in 2002 noted that AMAB were referred to a psychiatric clinic with a 10:1 ratio compared to AFAB(i.e., AMAB were 10 times more likely to be assessed for ADHD compared to AFAB). The conclusion of the study noted that based on the current ADHD criteria, AFAB were less likely to present overtly with psychiatric, cognitive, and functional impairment, which could result in a gender-based bias that is unfavorable for AFAB with ADHD. Though this information is well established, it remains a problematic bias. There is a whole generation of AFAB who were not diagnosed due to gender bias. An entire seminar could be dedicated to the "rise of ADHD in the USA.” Regardless, the gender bias that caused an entire population to be unassessed should be considered the priority to rectify in clinical practice today.

ADHD Quick Takeaways

The diagnosis of ADHD has evolved significantly over the years, from "Hyperkinetic Impulse Disorder" to "ADD" and finally to "ADHD."

The DSM-5 introduced three presentations of ADHD: inattentive type, combined type, and hyperactive type.

The DSM-5-TR in 2022 recognized ADHD as a lifespan diagnosis and included subtypes.

Gender bias has historically led to underdiagnosis of ADHD in females at birth ().

Males at birth (AMAB) were 10 times more likely to be assessed for ADHD compared to AFAB .

There is an entire generation of AFAB who should seek assessment and treatment if desired.

Disclaimer

This blog is intended for informational and educational purposes only. It does not constitute medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Please consult with a licensed medical or mental health professional before making any changes to your care, medications, or treatment plan. Every individual’s mental health journey is unique, and personalized guidance is essential.

Terms

AFAB-Female assigned at Birth, referring to sex not gender

AMAB: Male assigned at birth, referring to sex not gender

DSM- Diagnostic Manual of Mental Disorders, criteria used by mental health clinicians to diagnose mental health disorders

Resources